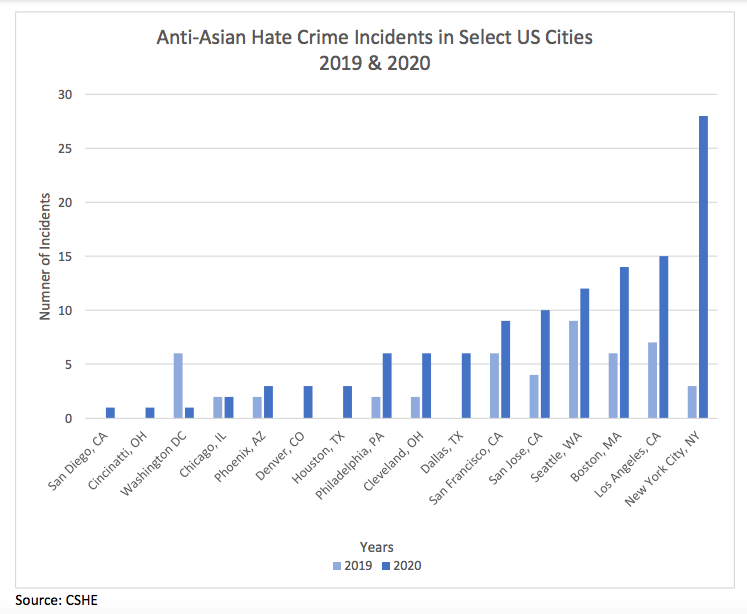

By Sophia Kim In the past year, and even more so in the past few months, reports of racism against Asian American people have become increasingly prevalent in the news and media. Of course racism against Asian Americans and Asian people has always existed, but it has gained more attention recently due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Because the first outbreaks of coronavirus occurred in China, some people have directed hateful, racist language and physical violence toward Asian people, especially those of Chinese, East Asian, and Southeast Asian descent, as blame for the pandemic. These days, I look at social media and become overwhelmed with anger and sadness as I see reports of people violently attacking Asian elderly in broad daylight and hear politicians throw around terms such as “China virus” or “Kung Flu” in professional settings. The increase in anti-Asian hate crimes first occurred in March and April of 2020 as the coronavirus spread to America. This increase is exemplified through a report by the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. According to the report, which took data from between 2019 and 2020, while hate crimes in the US’s 16 largest cities overall decreased by 6%, largely due to the enforcement of lockdown, hate crimes against Asian Americans have increased by 145%. In 2019, three anti-Asian hate crimes were reported in New York City, while 28 were reported in 2020. In LA, the number of hate crimes increased from seven to 15, and in Boston, six to 14. Additionally, Stop AAPI Hate recorded 3,795 anti-Asian incidents between March 19, 2020, and February 28, 2021. (STOP AAPI Hate is a nonprofit organization that was created during the COVID-19 pandemic that records acts of hate, harassment, violence and discrimination against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the US.) According to STOP AAPI Hate, verbal harassment, shunning or avoidance, and physical assault made up the top three types of discrimination reported. Attacks on Asian elderly have continued to make headlines in the news: Americans were especially appalled by a series of attacks on Asian elderly in Oakland, California, on January 31, 2021. One video shows a 91 year-old Asian man being violently pushed to the ground. An 84 year-old man was left dead from the injuries he sustained in a similar incident on the same day. Reports of attacks leave young Asian Americans, including myself, with a very real fear for their parents and grandparents. Although almost 3,800 incidents have been recorded by Stop AAPI Hate, many more incidents have gone unreported. According to Karthick Ramakrishnan, founder and director of AAPI Data, first-generation immigrants tend to under-report incidents of racism. A 2018 study by the Harvard Opinion Research Program similarly shows that Asian Americans report discrimination in employment, housing, and criminal justice less than other minorities in the US. Research has shown that language associating Asian people with the COVID-19 pandemic does impact Americans’ perceptions of Asian Americans. This is confirmed by a study coauthored by Rucker Johnson, a public policy professor at UC Berkeley. According to the study, terms such as “China virus” make Asian Americans seem more “foreign,” causing other Americans to act out in racism and violence. This issue has exacerbated the “perpetual foreigner” stereotype: the idea that Asian Americans will never fully assimilate into American society. This stereotype often prompts people to ask Asian Americans, “No, where are you really from?” or to tell them that they speak English "surprisingly" well. According to a study coauthored by Richard Lee, PhD, a psychology professor at the University of Minnesota, this stereotype is psychologically harmful and leads to symptoms of depression and lower self-esteem. It is clear how this type of racism can cause Asian Americans to question their place in society. Lee explains, “It essentially denies your sense of being American, denies your feeling like you belong here.” “China virus” language is not uniquely used by American politicians; politicians world-wide have perpetuated stereotypes and bias against Asian people through racist language. Early in the pandemic, one governor of Italy stated that Italians are generally good at hand-washing and showering, while the Chinese do not follow such hygienic practices and “eat mice live.” In addition, the education minister of Brazil tweeted that the coronavirus pandemic exemplified the Chinese government’s “plan for world domination.” Dehumanizing language like this may contribute to the increased rate of attacks, threats, and discrimination connected to the pandemic that Asian people around the world have experienced. The recent Atlanta shooting has created an uproar in the Asian American community amidst this global rise in anti-Asian hate. On March 16th, 2021, a shooter killed eight people in the Atlanta, Georgia, area. The shooter, Robert Aaron Long, first killed three women and one man at Young’s Asian Massage in Cherokee County, a suburb of Atlanta. The victims were Daoyou Feng (age 44), Paul Andre Michels (54), Xiaojie Tan (49), and Delaina Ashley Yaun (33). Rita Barron, an employee of Gabby’s Boutique directly next door, said she was with a customer when she heard clap-like noises, which were most likely the sounds of gunshots, and women screaming. The shooter next drove to Gold Spa and Aromatherapy Spa in Atlanta, where he killed four other people in less than one hour after the first shooting. The victims there were Hyun Jung Grant (age 51), Suncha Kim (69), Soon Chung Park (74), and Yong Ae Yue (63). In total, six out of the eight people killed were Asian women. While Long claims he killed these people because of his struggles with sex addiction in an attempt to deny that the incident was a hate crime, many following the story believe that these shootings were race and gender-motivated. The site of the first shooting was a strip mall in which other salons and boutiques surrounded Young’s Asian Massage, yet Long chose to target that particular business. He then picked out two other businesses in a separate location that also employed Asian women. When Cherokee County sheriff Jay Baker reported on the murders at a news conference following Long’s arrest, he talked almost sympathetically, saying that Long “was pretty much fed up and kind of at the end of his rope, and yesterday was a really bad day for him and this is what he did.” How can someone defend this murderer? Speaking about the incident in this manner is completely dehumanizing and wholly insensitive to the eight people who were killed and their families who are trying to cope with their losses. During this time of pain within the Asian American community, it is important that we as a society come up with solutions to lessen the racism that Asian people face in America. The “model minority” stereotype has often prevented society from addressing the racism that Asian people face. This stereotype perpetuates the belief that all Asian Americans are successful, hardworking, and academically high-achieving, and that they have adapted smoothly into American society. While this may seem like a “good stereotype,” generalizing Asian people in this way is demeaning and blinds people from the discrimination that Asian people face. Moreover, according to a study published in the Asian American Journal of Psychology, white people who hold the model minority myth are more likely to also have other negative views on Asian Americans. In assuming that all Asians are “well-off” and are not struggling as much as other minority groups, people make the struggles of Asian Americans invisible and exclude them from important conversations. I asked nine Asian students at CR North about their experiences growing up in their community as a minority. A majority of the students stated that they have faced racism in the form of microaggressions - “small” everyday incidents such as racist insults, nicknames, gestures, and comments. Several of the interviewees have been the target of phrases such as “Go back to China” and have been called “dog-eater” or “ch**k.” Others have had their race fetishized or used in “curry” jokes. While these microaggressions seem small in comparison to the physical attacks or hate crimes that have been widely reported in recent months, they have significant psychological impacts on those on the receiving end. As a result of these incidents, these students have grown up uncomfortable in their own skin, “ashamed of [their] ethnicity,” feeling “constant shame of [their] skin color,” “paranoid” of how others view them, “terrified to bring leftovers” from home-cooked meals in fear of being criticized for the smell, and feeling as if they “could be singled out in certain situations” because of their race. In addition to having to deal with the judgement they might face or already face due to their race, these students fear for the safety of their loved ones due to the actual or perceived racism in the community. One participant’s parents no longer feel safe going to a particular golf course after facing racist experiences there. Additionally, one interviewee stated that she fears for the safety of her grandparents who live in New York where many attacks against Asian people have occurred. Similarly, another student’s grandmother will be moving in with the interviewee’s family out of her home in Philadelphia due to the increase in Asian hate crimes in American cities. While I only interviewed a small group of Asian students from North, many of these students are deeply impacted by the racism that they and their families face. I also asked the students how they think we as a school or community in general can stop racism against Asian people. Several students commented that we should begin by better acknowledging racism, holding people accountable for their mistakes, and recognizing that microaggressions and terms such as “China virus” really are destructive. Whether in the media or in the incidents we witness first-hand, by allowing racism to go unaddressed, we are allowing the problem to become further perpetuated and normalized. Others suggested solutions that can be implemented in school. One student stated that education on racism should begin at the elementary and middle-school levels. Another answered that discussions on racism should take place more often in English or history classes so that all students have the opportunity to discuss these problems with others. One student stated that schools should take the initiative to educate students on “what classifies racism as racism and the harms of ‘jokes’ and microaggressions.” Another participant suggested that we could offer more Asian cuisine in the school cafeteria. While change will inevitably come slowly, we must continue to have these discussions in order to spread awareness of racism against Asian Americans and at least begin to break down harmful stereotypes and beliefs. If we want to build a more just and peaceful world, society must learn to see Asian people as humans first.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed